AST News Update January 2024: Practical Tips for Using Newly Formatted Tables 1 in CLSI M100 33rd Edition

1/22/2024

Priyanka Uprety, BD Life Sciences – Integrated Diagnostic Solutions, Sparks, Maryland, USA

Rebekah Dumm, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, USA

Janet Hindler, Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, Los Angeles, California, USA

Why were CLSI M100 Tables 1 revised?

In 1972, CLSI, formerly known as the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS), published “Table 1” in one of the earliest NCCLS AST documents. Table 1 was intended to help clinical laboratories decide which antimicrobial agents to test and report on specific bacteria. New drugs and new comments were added to the Tables 1 over the ensuing decades, but the format for these tables did not change. In the early 2020s CLSI decided to systematically reconsider the value of Tables 1 in light of the: 1) availability of new antimicrobial agents, 2) rise of antimicrobial resistance, including multidrug-resistant organisms (MDRO), and 3) introduction of antimicrobial stewardship programs to help manage appropriate antimicrobial use. The result was a major reformatting of Tables 1 and an expansion from 3 tables to 16 tables in the CLSI M100 33rd edition.1 Previously, each Table 1 contained several organisms/organism groups and many footnotes.2 Now, each Table 1 focuses on a single organism/organism group and contains only footnotes pertinent to that organism/organism group.

What should your clinical laboratory do with the new Tables 1?

It is suggested that each laboratory performing AST review the new Tables 1 in the context of antimicrobial agents currently tested and reported in their laboratory. Briefly, the steps might include:

1. Review the new Tables 1 together with the information that was added to CLSI M100 33rd edition that explains how to use these tables. These instructions are located at the beginning of Tables 1 as an “Introduction” and expanded in Section I (pages 2-7) entitled “Selection of Antimicrobial Agents for Testing and Reporting” of the “Instructions for Use” section of CLSI M100.

2. Review the antimicrobial agents currently tested and reported for each organism/organism group in your laboratory to see where gaps framed in the following questions may exist:

• Are there agents on your panels that are not included in the respective Table 1?

Example: Your panel for Pseudomonas aeruginosa includes ceftriaxone, but ceftriaxone is not listed in Table 1C and there are no breakpoints for ceftriaxone in Table 2B1. Ceftriaxone breakpoints for P. aeruginosa were eliminated in 2010.

• Are there agents listed on any Table 1 that are not included on your panels?

Example 1: Your panel for Stenotrophomonas maltophilia does not include minocycline, but minocycline is in Tier 1 in Table 1F. Tier 1 lists “antimicrobial agents that are appropriate for routine, primary testing and reporting.”

Example 2: You have been reporting ciprofloxacin routinely on all MRSA. In previous editions of CLSI M100, ciprofloxacin was included in the category (Category C) of agents that may require testing when resistant to primary agents. However, now ciprofloxacin is in Tier 4 in Table 1F where the suggestion is to consider testing ciprofloxacin only by physician request for Staphylococcus spp.

• Are your protocols up to date with suggested “cascade” reporting rules? Tables 1 suggest that results for broader-spectrum agents are suppressed for isolates that are susceptible to similar narrow-spectrum agents.

• Do your protocols address “selective” reporting rules, such as suppressing daptomycin on isolates from the respiratory tract?

3. Prepare a summary of the gaps that need attention.

4. Schedule a meeting with your antimicrobial stewardship program team (ASP) to determine if changes in your AST and reporting protocols are warranted.

Once it is determined that changes in AST and reporting protocols are warranted in your laboratory, what factors might be considered when addressing these changes?

1. Factors to consider if an agent will be eliminated from routine testing and reporting:

• Will removal of the agent from routine reports impact stakeholders beyond those discussed with the ASP?

• For which organism/organism groups will the agent be removed from routinely reporting?

• Was the agent tested and reported as part of a commercial MIC panel or as an individual test (eg, disk diffusion, gradient strip)?

• Is there a need to retain the ability to test the agent by physician request?

• Which ancillary protocols need to be modified (eg, QC, Infection Control, etc.)?

• Are any special changes needed in the data management system for reporting the agent (eg, any expert reporting rules for which the drug has been included, or any infection control guidance linked to the particular antimicrobial agent report)?

2. Factors to consider if an agent will be added to routine testing and reporting:

• For which organism/organism groups will the agent be routinely tested and reported?

• Is the agent currently on the routine MIC panel(s) but suppressed for the organism/organism groups where the change is needed?

• If the drug is not on the routine MIC panel(s), will it be most practical to select a new MIC panel or test the agent offline?

• Has performance of the agent been previously verified/validated, or will a verification/validation be required?

• Will any selective or cascade reporting rules for the new drug or other drugs be needed as a result of this change?

• What changes will be needed within the data management system? How long will it take to make these changes?

• Which ancillary protocols need to be modified (eg, QC, Infection Control, etc.)?

• Will the agent be added to the next publication of the facility’s annual antibiogram?

• How will the change be communicated to laboratory staff and recipients of AST results?

• Will the agent be removed from the next publication of the facility’s annual antibiogram?

• How will the change be communicated to laboratory staff and recipients of AST results?

What would be an example of applying the guidance in the new Tables 1?

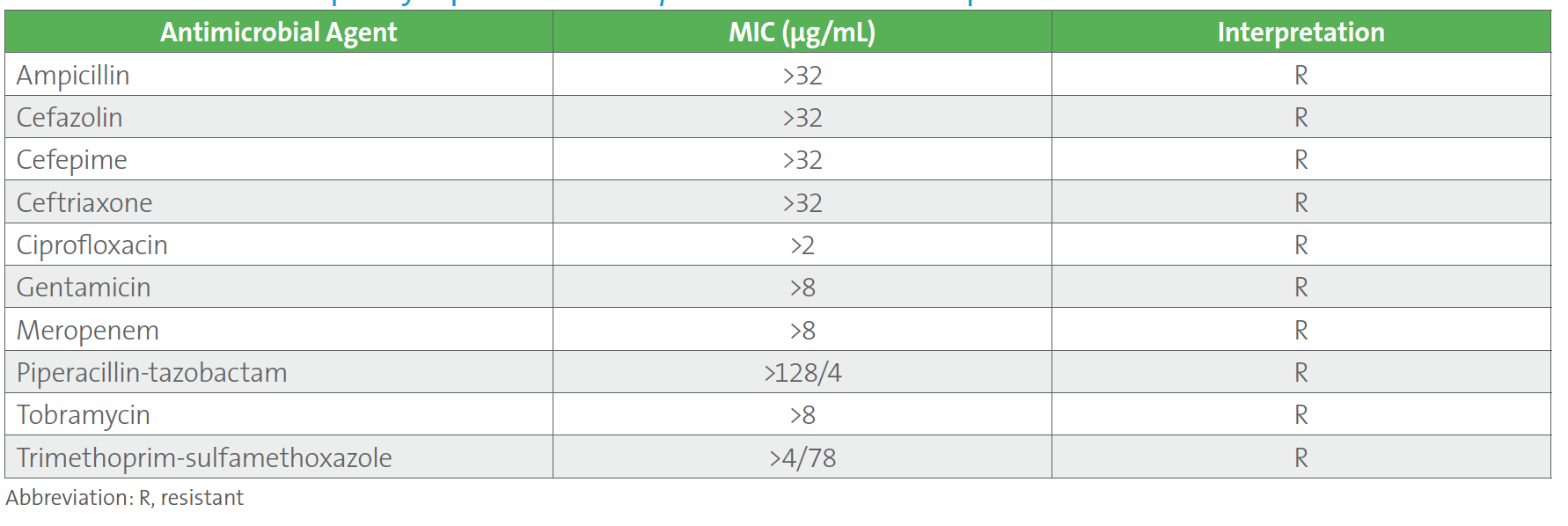

The following case may be considered. Two sets of blood cultures from a patient who was recently transferred to the hospital from a long-term care facility grew carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae (refer to Table 1.). Results from the laboratory’s routine automated MIC panel are shown below. This was the third case of carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae within a month for this laboratory, and the sixth case in the past 12 months for which an isolate of Enterobacterales tested resistant to all antimicrobials on the automated panel. As with the other cases, the provider asked that the isolate be tested for ceftazidime-avibactam, which was performed using an agar gradient diffusion test since ceftazidime-avibactam was not on the automated MIC panel.

Table 1. Antimicrobial Susceptiblity Report for Klebsiella pneumoniae in Case Example

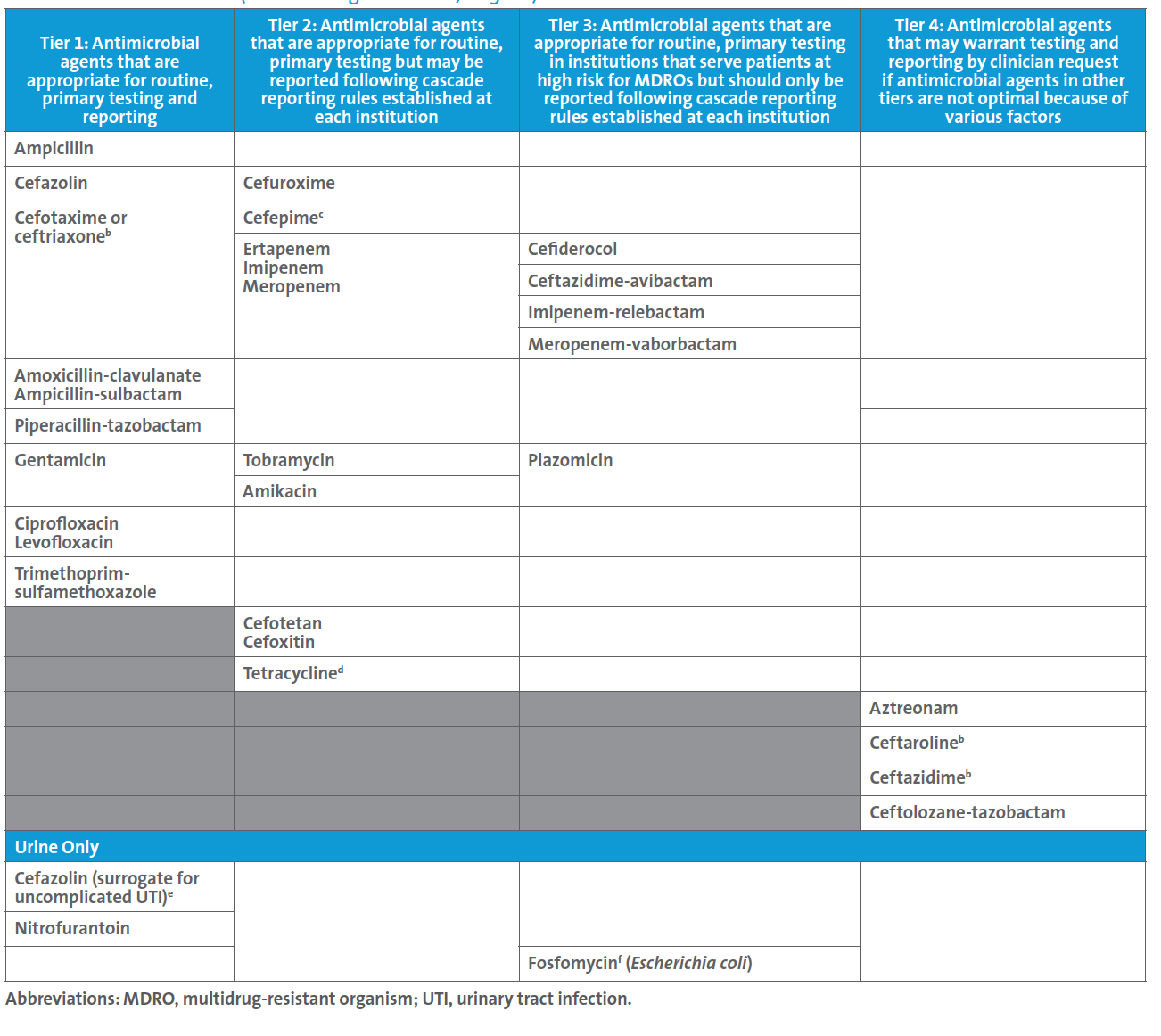

A follow up to this case led the ASP to request a review of the laboratory’s testing and reporting protocols, at which time the new CLSI M100 Table 1A (see below) for Enterobacterales was discussed. The ASP team shared the Infectious Diseases Society of America’s guidelines for managing patients with MDROs.3 It was noted that CLSI suggests that routine, primary testing of one or more of the β-lactam combination agents should be considered for reporting (ie, Tier 3) for institutions that serve patients at high risk for MDROs. Although the laboratory cascades to testing ceftazidime-avibactam on carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE) the decision was made to find a new AST panel that contained ceftazidime-avibactam for testing and reporting because:

• There is a one-day delay in reporting ceftazidime-avibactam results when cascading to agar gradient diffusion testing. Most patients harboring CRE are very ill, and AST results are critical in guiding the most appropriate agent(s) for treatment as soon as possible.

• There were reports within nearby hospitals of metallo-β-lactamase (MBL)-producing isolates of Enterobacterales; this is important because ceftazidime-avibactam is not active against MBL-producing isolates.

• This institution serves patients at high risk for MDROs, and this reporting approach corresponds to suggestions in CLSI M100 Table 1A.

Table 1A. Enterobacterales (not including Salmonella/Shigella)a

In conclusion, laboratories should review the new Tables 1 in the updated CLSI M100 document and discuss testing and reporting changes with appropriate stakeholders such as ASP.

References

1. CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 33rd ed. CLSI supplement M100. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2023. Access here.

2. CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 32nd ed. CLSI supplement M100. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2022.

3. Tamma PD, Aitken SL, Bonomo RA, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America Antimicrobial-Resistant Treatment Guidance: Gram-Negative Bacterial Infections. Infectious Diseases Society of America 2023; Version 3.0. Available at https://www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/amr-guidance/. Accessed January 16, 2024.